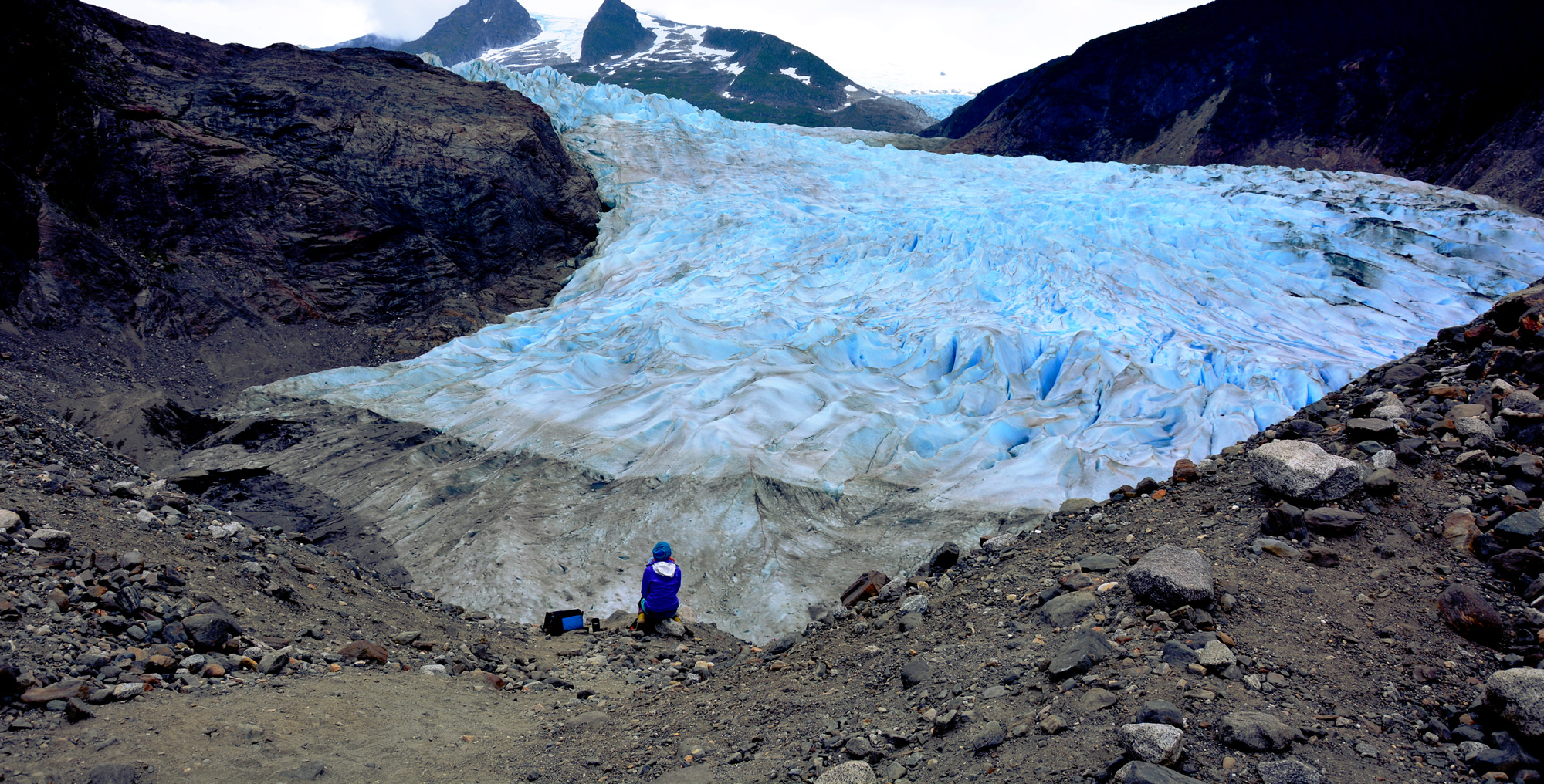

As I gazed upon the ice, I could barely breathe for wonder.

It was massive, a living landscape of white, accented by a deep, solid blue. And dirty, covered with rocks and sand and the leftover dust of ages of moulding the earth to its power. The rocks have been no match for the ice over the centuries. They crumble, and they catch, becoming frozen in the walls, surrendering. The ice is a museum, preserving the stones that it captured a forever ago, becoming solid windows to the past. The landscape stretches on and it anchors in the mountains and dominates the panorama, as the human mind is barely able to comprehend its vastness. The air is cold, noticeably colder than the mild Alaskan summer day that engulfs it. The world is wet, wet that you mistake for rain as you inch into crevasses and caves, whose majesty only continues to astound you with every centimeter you traverse into their territory. It is enough wetness to feed whole rivers. It is loud, as the water from every side and surface rushes by to get away and continue to its destination, only to be followed by more frigid liquid.

As I stand there, gazing upon such a dignified, imposing figure, I feel very insignificant. I guess experiencing a natural wonder as powerful as a glacier - up front and personal for the first time - will do that to you.

We followed the signs. It was an official trail, a marked path that went up and down, windy and steep. Eventually we came to the part where our path and the official trail parted ways, upon a handwritten sign that told us where we wanted to go. We followed in the footsteps of those who had come before us, a smaller trail, often marked with only a brightly colored ribbon on a tree branch. We got closer and closer to the glacier, as the world got colder and colder. The vegetation changed constantly, eventually giving way to just rocks that made the path more of a distant shadow than anything else. As we made our way closer, the rocks tumbled, and we were careful. This is a part of the world that has only recently began to see the light of day, where the ice has receded enough to set the rocks free. Ten years ago, this was all covered in ice. Now, we make our way down to the vast whiteness. We worked hard to get here. Many people visit the Mendenhall Glacier up close by flying over it in a helicopter for a lot of money. We walked to it for free, working our legs and pumping our muscles.

It is hard to tell when you are standing on a glacier. Everything is covered on the edges with dirt and rocks, you can barely tell where the world officially turns to ice. Would I break it? Would I cause harm to this noble creature? I could never break it. It is vain to even have considered the thought. Nature is mighty. This is one of nature’s most powerful expressions, it in its full, all-encompassing design. Every rock that makes me jump as it falls from the icy ceiling when I dare to enter its caves has been resting in its spot for ages - I am fortunate enough to see the moment of its release. The amount of water that this landscape is composed of is incomprehensible to me.

And yet, it is wasting away before my very eyes. We watch the water drip and drop and wash away, creating the very caverns that we are standing in. Coming to Alaska, I was told that this or that river is fed by this or that glacier, completely. And I just didn’t understand. How can a glacier feed a river? A river, wide and deep as any, flowing day in and day out, continuing on its path until it gets to the ocean. It continues, on and on, long having earned its place on the map. Nothing can melt enough, produce enough water, to do that, not so fast. It should be gone, long gone, by the time I was contemplating this conumdrum. And now, with the miracle of this question before my eyes, I finally understood. Standing in an ice cave, there is water everywhere - living, flowing, draining. Every pore sweats of it.

So many things I had never understood about these majesties before. Even the day before, gazing at this same glacier from the visitor center over a mile away, my tiny little mind could not comprehend the vastness of this being. The guides explained how much closer it was ten, twenty, fifty years ago. And how it had been receding at an ever-alarming rate. Mendenhall receded almost two miles in the last fifty years. It is now about thirteen and a half miles long. You can read all you want about global warming in a textbook, hear reports of it on the news or politicians debating its existance, but this is a differnt story. In summer, glaciers melt. They always have. But now, they are slowly and steadily dying, around me as I stand. I contribute to this, my house emits gasses that help to kill this creature. This icy landscape is forever changing - if you travel to Mendenhall and attempt to capture the same image featured in this article, you will fail. The glacier will have changed its face by then. My grandchildren may very well grow up in a world where the natural majesty that left me nearly dropping to my knees is only of the past.

I will never forget this sight. The power of nature and my own deceiving triviality.

Glaciers are magnificent.